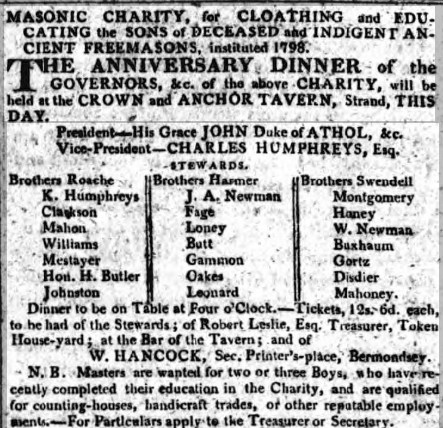

When I first came across William I pictured him as reasonably well off since he was literate and a member of the Freemasons. He’s mentioned in a newspaper report on the 14th of April 1809 attending a Freemasons dinner at the Crown and Anchor on the Strand in London. William was a member of the Freemasons until June 1822.

When William joined the Freemasons on the 4th of June 1804 his occupation was recorded as a gentleman. An occupation of gentleman in Victorian times typically meant that the individual didn’t have to work for a living as they were independently wealthy. However one month later, on the 4th of July 1804, he is quoted in court proceedings as travelling to Maidenhead to find J. Gaimes in his role as a clerk for Mr. Humphreys.

William died in 1844 so he only appears in the 1841 census. His children’s baptism records are the best means of understanding how his life was changing over time. Where recorded, his occupation switches between gentleman and clerk. In 1820 his occupation is recorded as a gentleman on the baptism records of his children Frederick Augustus (1820 - 1836) and Emma (1820 - 1882). For the next 17 years William’s occupation is recorded as either a gentleman or clerk on his children’s baptism records.

It seems mostly likely that William was a clerk and that his occupation being recorded as gentleman was either wishful thinking or a transcribing error. William was a clerk for Mr. Humphreys and had a long professional relationship with him. In late 1825 William wrote a letter to the king pleading for clemency for his son William. At the end of the letter Mr. Humphreys adds a character reference for William stating that he has worked for him for 23 years.

In the same letter we get an insight into William’s home life. William was unable to look after his son, William Junior, because of his work. He also states that William Junior was looked after by Mr. Humphrey’s sister Penelope Cown from the age of 2 (approximately 1811) until she died in 1817 when William Junior was 8. Given this information I think that Mr. Humphreys is Charles Humphreys (1750 - ?) and his sister is Penelope Humphreys (1761 - 1817) who married William Corne (1755 -1802).

An indication of the regard with which William held Penelope and Charles is that his sixth son Joseph was given the middle name Corne and his seventh son Henry was given the middle name Humphrey.

Returning to the newspaper article the Vice-President of the Freemasons is none other than Charles Humphreys. In William’s letter to the King in 1825 Charles Humphreys states that William has worked for him for 23 years. This would mean that William started working for Charles in 1803. William joining the Freemasons in 1804 would be consistent with Charles encouraging William to join.

When I first came across William I thought he must have been reasonably well off as he was literate and his occupation was recorded as a gentlemen when he joined the Freemasons. Following further research his occupation is variously recorded as gentleman throughout his life while he is clearly working as a clerk. So while it’s clear he wasn’t a gentleman was he well off? From what I understand clerk’s pay could vary widely - 1. Charles Dickens’s Christmas Carol was published in 1843 in which Bob Cratchit, a solicitor’s clerk, became a byword for poverty. Given William and Charles’ long working relationship of over 20 years along with William’s apparent naming of two of his sons after Charles and his sister Penelope it would appear that William thought well of Charles. Despite this William doesn’t seem to have had much money as three of his sons (William, Charles and Frederick) were convicted of stealing and sentenced to be sent to Australia. Two of his sons (Henry and Thomas) joined the army. From what I’ve read joining the army in Victorian times was done out of necessity rather than choice.

All of this points to William not having much money. He doesn’t appear to have owned property as his children’s baptism records record different addresses mostly in and around Hoxton. So while there is evidence of him being a clerk and a Freemason there’s no evidence of him being a gentleman.

-

Geoffrey Best, Mid-Victorian Britain 1851-75 (Fontana, 1979), 107-110. ↩